When Benjamin Nauleau traded his bijoux Berlin apartment for a red brick 19th-century former schoolhouse in Havelland, one of Germany’s most remote districts, it ignited a radical change in his relationship with nature. While he once spent his days hunched over a computer editing pictures in his work as a photographer, since the 2019 move Nauleau has led a far more balanced lifestyle: tending to the garden, wild swimming and trout fishing in the nearby river, and gathering everything from wild herbs to garlic from the region’s rich store cupboard of flora and fauna.

Nowadays, the only time he picks up his camera is to capture the beautiful baskets he weaves from locally grown willow and foraged hazel wood, under the moniker Die Weiderei.

A third-generation weaver who grew up in Vendée, Western France, a place where basketry was once part of village and farming life, Nauleau believes we are entering a golden age of the craft. “Basket makers are very lucky right now, because society is starting to understand that we need to go back to natural materials and handcrafted objects – we are riding that wave.”

“Society is starting to understand that we need to go back to natural materials and handcrafted objects”

Benjamin Nauleau

Sarah Loughlin, who runs Hopewood Baskets together with Marcus Wootton, feels similarly in tune with the seasons and her heritage. The pair work from a garden studio at their home close to the Wyre Forest in Worcester, UK, where their work has a rich history. “As a craft, basketry is older than ceramics. One of the first things humans would have made is baskets to hold things in,” says Loughlin, whose designs include a foraging basket, forged from willow in a French randing pattern, designed to stow away precious cargo from woodland or hedgerow excursions.

At one time people would have made particular baskets to contain specific finds, from apples to potatoes; fish baskets came in different sizes to reflect the different weights; there was even a duck nesting basket.

Loughlin, who originally trained as a Montessori teacher, gathers hazelwood from the local oak and birch forests to make her baskets, and these wild finds have become an intrinsic part of what is an all-encompassing, slow-spun endeavour. “I get totally lost for hours in the hunt for the perfect stick,” she says. Working with willow, much of which comes from a local coppice, Loughlin is also increasingly hands-on with the harvesting, deliberately incorporating the incisions from the hand-cut crop as part of the basket’s story.

For Loughlin, there’s a sense of pure wonder in her craft. “I’m always amazed by the fact that you can start with a pile of sticks, and with only a knife you can end up with something useful and beautiful that holds and protects things” she says.

“As a craft, basketry is older than ceramics”

Sarah Loughlin

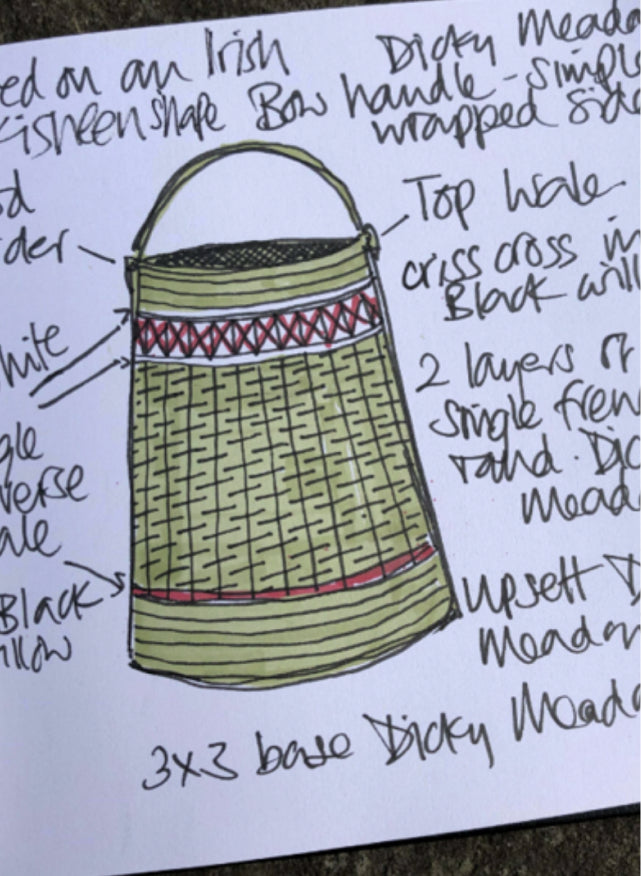

This idea of protection also sits at the core of the creations of Rachel Bower, whose rainbow-hued basketry includes a take on a traditional style known as the Aran Island Kisheen. The story goes that this particular basket was conceived with inward sloping sides to secure its contents from spilling as the women walked through the fields – across dykes and over dry stone walls – to take the menfolk their lunch. So enamoured was Bower by the tale, she even makes a miniaturised version for children, as a way, she says, to introduce the next generation to the joys of foraging.

Living in the wilds of Angus, the bounty of northeastern Scotland’s beaches, woodlands and mountain ranges are – with the landowner's permission – hers for the taking.

As well as blaeberries, Bower gathers larch and once a year, when it’s ripe for harvesting, red dogwood, to add a burst of colour to her baskets.“You have to catch it at just the right point,” she explains of dogwood, which serves as a woven celebration of her local landscape.

Travelling alone across the landscape on these foraging walks is, she says, utterly liberating. Working mostly with willow from a local friend’s smallholding, Bower weaves outside her timber-framed garden workshop, interrupted only by the spring arrival of the queen bee and the occasional murmuration of starlings. “Basketry is incredibly connected to nature – it’s a plant material that you can collect, it’s available to all without the need to buy it, as long as you know how to use it and harvest it,” says Bower. “It’s very freeing that you can go along and pick something, process and actually use it.”

“It’s very freeing that you can go along and pick something, process and actually use it.”

Few weavers are more deeply committed to the ancient rituals of their craft and its links to the land than Felicity Irons. One of the last remaining practitioners in Europe, Irons is a self-taught rush weaver who established her workshop, Rush Matters, in the 1990s. When her local Cambridgeshire rush cutter died, his brother encouraged Irons to take on the practice. “He gave me a two-hour lesson in rush cutting and that was that,” she says. “I’d never been on a river before – it was terrifying – but I was immediately hooked.”

Irons soon realised that the English rush market was dominated by the Dutch rush, so she took on extra helpers and began distributing her crop more widely. Decades on, once a year, typically in late June, Irons heads onto the River Nene and along the River Ouse in her punt, to harvest rush.

Cut by hand with a three-ft scythe, their daily haul of some two-tonnes of rush is tied into bundles, then lined up along the hedgerow outside her workshop in a 14th-century barn to dry for anything up to ten days. “When we’re on the non-navigable parts of the river where there are no people it’s very special” she says. “There are kingfishers and mayflies, moorhens, swans with their cygnets, and the occasional otter.”

Irons is continuing an East Anglian tradition that dates to the 1700s, only falling out of fashion after the Second World War. Her rush flooring and tableware is beloved by everyone from Jasper Conran to The National Trust and the Metropolitan Museum.

“I love that this humble plant that no one notices on the river can become this practical object that sits in both ordinary and extraordinary homes all over the world” she says. “Bulrush has its own inherent beauty.”

And while we can't all live in remote places, the pieces these modern artisans produce bring a little part of their inner peace into our homes around the world.

“I love that this humble plant that no one notices on the river can become this practical object”

Felicity Irons