Sommerso, Millefiori, Incalmo, Battuti: if the time-honoured techniques of Murano glassmaking sound like a list of Renaissance poets, it’s because this is an art form versed in centuries of craftsmanship. And these are just a few of the fascinating methods and details that make Murano glass determinedly unique. Dating back to the Roman era in Venice, glassmaking is to Veneto what papermaking is to Amalfi: its most celebrated and valued of traditions, and one whose legacy continues to be written.

“The techniques the maestros in the furnace developed and still use are just amazing,” says Marie-Rose Kahane, who launched Yali Glass in 2008.

Meet the Maker: Yali

Among other methods, Kahane has adapted the traditionally ornate filigrana technique, which has a fine white line running through it almost like a textile, to make a simple cylinder. “Transforming something is what we do all the time; there’s a bridge building between the past and the future.

”Keeping the legacy of Murano glassmaking alive demands an embrace of experimentation rather than attempting to reinvent the wheel, says Giberto Arrivabene Valenti Gonzaga. He started his eponymous brand, Giberto, 18 years ago as “a hobby” to complement his main job as an insurance broker and has since revolutionised the rigàmenà technique to create a teardrop on the rim of his signature Julia glass.

“It’s hard to invent something because they’ve been making glasses for a thousand years,” he explains. “To do it is very difficult, but when it comes it’s fantastic. And you never know how it’s going to come out until its done – glass is a material where the limits between amazing beauty and [it looking] cheap is very thin.

”That Kahane and Gonzaga were able to indulge their passions at all is testament to how far the art of Murano glassmaking has come.

After the government moved production to Murano from central Venice in the 13th century for fear of the scorchingly hot furnaces (which can reach over 2,000 degrees celsius) setting the stilted city alight, it became a highly secretive affair.

“Murano is my creative and intellectual escape and paradise”

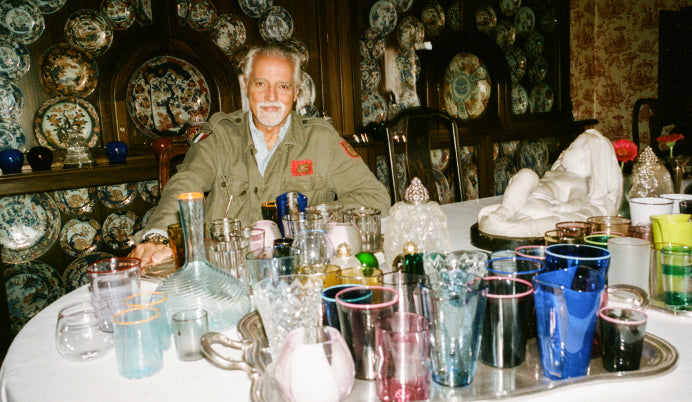

Giberto Arrivabene Valenti de Gonzaga

Meet the Maker: Giberto

Glassmakers were prohibited from working outside Murano and threatened with a death sentence for disclosing the special recipe of silica, lime, soda, and potassium or the minerals mixed to make different colours. Their blowing, twisting, turning and dipping methods also remained firmly under wraps, while intermarriage between Murano residents and those on the mainland Italy was also firmly off limits.

Such restrictions – and suspicions – have since eased off, although the prestige in the profession remains strong.“It was quite difficult at the start, because it’s a closed environment,” says Kahane of the island, which currently has around 100 glass factories. “But a lot of it has to do with friendship and establishing a real rapport with the glassmakers you work with; 13 years later we work with six different furnaces.”

Design inspiration aside, it is still in these furnaces where the Murano-making magic happens. In contrast to the exacting final product, in its raw state the glass has a mesmerising malleability that allows it to be shapeshifted several times. Huge scissors, called tagianti, “cut through hot glass the way you would a piece of velvet”, explains Kahane. Each set is made in Murano (of course), and each is as unique to a maestro as a set of knives to a chef.

Murano glass is, says Kahane, a constant dialogue with the material and the glassblower and the time it takes: “You can’t be in a rush! The beauty of it is that the pieces are made one by one in a non-mechanical way, so it takes longer. A glass that has a stem, for example, needs at least three people to make it; such is the physicality of it with people moving around, it’s like a form a ballet.”

Meet the Maker: Venini

Over the years, Murano has become synonymous with many designers and masters, with the 20th Century proving to be something of a heyday for Murano glass brands – among them Giacomo Cappellini and Paolo Venini. They established Venini in 1921, creating a Murano icon in the Veronese vase and making the “mano volante” (flying hand) technique world famous with the Fazzoletti vase, a collaboration with Fulvio Bianconi that took its name from the handkerchief shape it depicts.

In 1923 Venini was joined by NasonMorretti, a brand founded by brothers Ugo, Antonio, Giuseppe, Vincenzo and Umberto Nason. Making its name for achieving an intensity of colour, as it approaches its centenary year, it is still the only Murano glass brand that can produce 22 kinds of green and nine kinds of blue. “Every new collection we launch has almost six different colours – sometimes 12,” says Piero Nason, one of the third generation members of the family business.

“This is the power of Murano glass. We look at our tradition to make invocation for the future – all the products we make for the future start from what we have done in the past.

”That such beauty comes from this beguiling corner of the Venetian lagoon is no surprise, as the surrounding waters and constant state of fluidity find a synergy with the vessels created there.

“Murano is my creative and intellectual escape and paradise,” smiles Gonzaga. “When I’m in a bad mood, I go to Murano. I walk, I design first in my mind and then put it on to paper. It’s a moment of freedom for just me and my glass.”

Words by Scarlett Conlon